It was a hug. Just a hug. But a hug is never just a hug.

A hug is often an expression of compassion and endearment — or for me that time, a source of confusion and an unexpected way of ending a night that presumably had intentions of going elsewhere. They weren’t my intentions, but leave that part alone for a moment.

College nights like that one have been written about before — way too many times — and they pretty much end the same way every time. We would go to a formal, have a great time, dance, drink more than we should and find ourselves waking up next to one another. Superficially, I appeared suitable to play the part and willing to see the night through to the end.

Get off the sidelines and into the game

Our weekly playbook is packed with everything from locker room chatter to pressing LGBTQ sports issues.

Yet, I knew there was always a possibility of that night ending in a way that later turned out to be very unpopular.

For the first time in my life I was having to dodge a shitstorm of questions prying at my deepest secret — and yes, mocking the way in which I chose to end the evening. In other words, a hug was going to be it for me.

And that just wasn’t acceptable. I felt vulnerable — not just that night but, increasingly, all of the time. The vulnerability showed up in bouts of defensiveness and anger. I worried all the time. I worried about protecting who I longed to be and who I wanted others to understand me to be.

The one thing I didn’t take time to worry about was the real problem — what about this situation was making me so angry?

I’d built a good facade — careful, strong, seamless. And I thought I knew how to defend it. But honestly, the anger and the fear came from expending all the energy it took to defend it. I could sense others beginning to form conclusions.

I could sense their confusion and their questions, just as I knew that my date that night — not just a beautiful girl but a good person — had her own questions. They would have been something like, am I not getting to you in a way that’s worth more than a hug? You’re a cute guy. You’re this big hockey jock.

Is it me?

I could have answered her confusion and my own with a single honest sentence.

I could have said, it’s not you. I hope I’m all those things — a good guy, a nice-looking guy, an athlete.

I’m also gay.

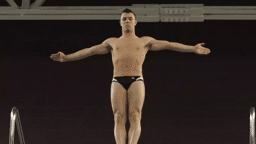

But how could that be? A hockey player is an athlete to the 10th power, presumed to be not just skilled but crazy aggressive, an apex predator. So how could a boy who’d played hockey all his life, a boy who was now a man, not fit all those traditional definitions of a guy’s guy?

All I knew was, I didn’t. And I was ready for that facade to fall.

I was pushed onto the ice when I was 4 and all I can remember was crying and screaming, “The ice is too slippery!” Duh! Well, as a 4-year-old this could not have been more terrifying. But when I got to the Peewee level, I grew into hockey. It got its hooks in me. It took on a new social dynamic with its own colorful and profane vocabulary.

My coach wanted us to be independent, so he laid out some ground rules. Parents were no longer allowed in our locker room; the only thing that meant to me at the time was I would have to start tying my own skates. He was going to treat us like adults. The locker room door would close, and it was then up to a bunch of 11- and 12-year-olds to say anything on their minds. And we were all boys coming of age, so nothing was off limits.

It wasn’t the first time I’d heard the cruel use of “faggot” and “gay.” But it was the first time that it felt personal. Hockey was that kind of sport. It was more than the ice that was dangerous.

On the ice was where I felt free. I could forget the internal battle questioning my sexuality.

But I still loved playing the game. On the ice was where I felt free. I could forget the internal battle questioning my sexuality. I could turn all that aggressive questioning outward, to the game, where it was welcomed.

Then, I got older. High school was when my love and willingness to play hockey began to be replaced by something else. I can only call it fear.

My teammates were getting heavily into their girlfriends. And my spin-the-bottle and in-name-only crushes were not at all on the level of what was being tossed around the locker room by this stage. That was when I began to keep to myself, fostering an image of myself as a guy who didn’t talk trash.

I had the desire for the esteem that came from some cool anecdote about me as a lady’s man, but could I tell a lie, like that? Sure I’d told my share of lies in my life — to get out of trouble, to impress somebody. But what if I had to defend that lie?

Worry and fear ate away at my love of the sport.

I quit.

I told my confused parents, who were caught off-guard by my decision, that I was burnt out.

But what could I tell them? My dad was a referee. My mom was the hockey mom incarnate. Their Sundays at my games were as religious as any other family going to church.

I remember the letter my dad wrote me after I quit, each paragraph recalling a different memory from my playing days. He wanted to make sure that I was making the right decision. It was clear that he was in slight opposition although he is not the kind who would ever force or forbid. And as for me, I hated this time; I didn’t want to be different. I was fairly sure by then that I was gay. Would this drag me away from being the child my parents had always been so proud of?

I started to golf then, and I took it seriously. And I was good — but not really that good. I was sought after, to play collegiate golf at the University of Northern Iowa. Seasons went by, and I realized I was kidding myself and the world in more ways than one. Then came the day that I broke down and tearfully expressed to my parents that I couldn’t follow through.

I wanted to excel. I wanted to love my sport.

In short, I wanted to play hockey again.

For the next three years I did just that at University of Iowa. Sure, I was happy to be back on that slippery surface. But the ulterior motives for picking up the game again were never lost on me. I knew this would probably make the transition into college easier. It would lead to camaraderie and friendships.

But it would also tend to deflect any speculations about my sexual identity.

I was a hockey player. Enough said.

And I thought it would all work out. But I was taking all kinds of hits. Not only was I suffering significant structural problems in my legs and hips, which just couldn’t stand up any more to the demands of play, my mental health was being checked even harder.

I had one saving grace.

For years my dad tried to convince me to be a referee. He always prefaced it with how nice it was to make some extra money. I remember thinking to myself why anyone would willingly be a hockey referee. Why would anyone willingly be yelled at, abused and castigated by the crazy parents of some 8-year-old convinced that I was ruining their child’s career? I could think of enough ways to make myself crazy without that.

Apparently not. I was 19 when I started refereeing hockey — the best decision I have ever made. I loved it. This decision gave me the freedom to stay involved in the game when playing was no longer an option. It gave me other perks as well, traveling the country working for the North American Hockey League, United States Hockey League and collegiate leagues among others.

Probably the most important aspect of me being a referee was being selected to work for the Officials Development Program. I was one of many officials staffed under this program and was witness to the pivotal development of newly established rules. It was exciting and it was fun.

But it also was personal.

The word “faggot” was no longer a permissible word in hockey and could not only be penalized, but cause for removal of the player from the game.

Written clearly in front of me, in black and white, was proof that the world was changing: The word “faggot” was no longer a permissible word in hockey and could not only be penalized, but cause for removal of the player from the game. To know that the program that I refereed for was aware of the harm surrounding that word was powerful. For the first time I remember feeling as if I was settling into a place of comfort and self-acceptance.

A year into working for the program, I met Dalton, a fellow referee who would become one of my best friends. Aside from him being very easy to get along with, he was also gay. I think I always knew that he would be the first person I would tell, but never sure when that was going to happen.

Months before the start of 2017 hockey season, the North American Hockey League was having a combine in Minnesota and bringing a group of referees along to officiate. Every trip we would all pick a room to drink beer and tell crazy stories of past games to fill our time. For me, something just felt different this time, but not in a bad way. During those bull sessions, it seemed all I could hear were the questions directed toward Dalton asking him how his boyfriend was and when they would get to meet him.

The other guys weren’t mocking Dalton. They were genuinely cool about his relationship.

Right then, I realized that I didn’t need any more reassurance that things would be OK if I came out to him — so I did, that night.

And then, the wall really fell. I progressively came out to others, mostly family and close friends. This was all so new. Was there a certain way I should act? I had no clue! I certainly didn’t know how to navigate the gay dating landscape. I didn’t even have a vision of what type of man I would want to date.

Nevertheless, I took a leap. Through a mutual friend, I was made aware of a guy named Steve Stull. Apparently, we had a lot of the same interests. Steve and I are approaching two and a half years of our relationship, and we have our own home. Our families are crazy about each other. I guess that friend was right!

I put our relationship on Facebook, and I could not believe the tremendous amount of support that came in from even more friends and family. I wish I could say it was all rainbows and butterflies, but there were those that expressed their opposition — I was OK with that. I hope they can read this and realize I didn’t need their seal of approval. I am me and I am damn proud of it.

Not long after in 2018, my dad won a national award for the organization of public officials he is part of — a group of hardened guys and women the professional equivalent of hockey players. When he gave his acceptance speech, he looked down and mentioned how proud he was that I’d come out to my family just a few months before. The whole group of them cheered.

Within a week of my posting on Facebook, four people gathered the courage to come out to me — including a couple of referees. This meant the world to me and I knew one day I would want to take the time and write my own story. I guess that time is now.

Bravery, perseverance and strength are not linked to your sexual identification.

Looking back, I wish I could have come out sooner. Maybe I should have had the courage to grow up redefining what male athletes could look like — and could be. But everyone comes to understand in his own time, and bravery, perseverance and strength are not linked to your sexual identification. Being who you truly are is courage made real.

Being out is a huge decision for any athlete because what male athletes traditionally stand for in our culture is the pinnacle of traditional masculinity. But I guess that definition — about what it means to be a man — needs to change to be more inclusive of all kinds of men. I share my story in hopes that if you read it and you need to find the self-empowerment to be OK with being gay, I’ve been there. I have your back. Nobody deserves it more than you do!

You’ll find out: You are loved. You are respected. You don’t have to pretend to be anyone except the man you are. If I don’t know anything else, I know this much is true.

Gordie Mitchard, 28, is a 2014 graduate of the University of Iowa where he played college hockey for three years and was team captain. Thereafter, he pursued his refereeing career working youth, juniors, college, and semi-professional leagues. Currently, he is completing his master’s degree in Occupational and Environmental Health — Ergonomics from the College of Public Health at Iowa. He can be reached on Instagram @gordball_09 or via email ([email protected]).

Story editor: Jim Buzinski

If you are an out LGBTQ person in sports and want to tell your story, email Jim ([email protected])

Check out our archive of coming out stories.

If you’re an LGBTQ person in sports looking to connect with others in the community, head over to GO! Space to meet and interact with other LGBTQ athletes, or to Equality Coaching Alliance to find other coaches, administrators and other non-athletes in sports.